The presidential election of Donald Trump occurred due to many elements, including opposition to new, bold, and unusual ideas: the excesses of the woke movement and gender ideology, which some see as contrary to historical and common-sense perspectives.

Recognizing the complexities and errors within historical evolution is one thing; trying to completely rewrite history according to contemporary sensibilities is another. Granting full rights to people with diverse sexual preferences aligns with much of human experience, but denying inherent bodily distinctions and tampering with young bodies are controversial propositions. Many Americans either did not comprehend or weren’t interested in those ideas.

A return to common sense should also involve acknowledging that liberal democracies are not a predestined human endpoint but rather a complex historical development. History and politics are crucial, not mere accessories. The free market and capitalism, which fueled significant technological and societal progress over the past two centuries, are complex systems that require careful political stewardship and direction.

The slogan “Make America Great Again” seems also to signal the beginning of the end of the Westphalian order, which was based on a balance of powers. The Westphalian order disrupted and ultimately ended the dominance of the Holy Roman Empire and the Papacy, which had dominated European history for over a millennium. The US historically emerged through the balance of powers, yet at this moment, it may not need it. After all, the means to keep power differ from the means to gain it.

Westphalia and the Papacy’s Demise

The Peace of Westphalia in 1648 declared that the Habsburg Empire, supported by the Papacy, could no longer control or guide all continental Europe and the global expansion of European powers. The Habsburg dynasty had two centers: Austria and the Iberian Peninsula. France, although Catholic, had a king initially Protestant and primarily sided with Protestants. Additionally, Spain and Portugal expended the wealth from their international trade on luxuries and churches, whereas thrifty Protestants invested their capital in expanding commercial and industrial endeavors.

Max Weber said this signified the Protestant spirit of capitalism, but it was perhaps more than that. It represented a new geopolitical order without papal arbitration, which had united Europe for a millennium. Freed from the Pope’s arbitration at Westphalia, Protestants believed nations could resolve disputes directly through diplomacy or war. This led to the gradual sidelining of the Papal State from political centrality, marked by two more significant events: the French Revolution in 1789 and the Papal State’s conquest in 1870. Between 1648 and 1789, the Church, expelled from the Protestant world, continued to play an essential role in Catholic countries.

The 1789 French Revolution attempted to remove religion from politics and more radically subordinate religion to governmental authority. Napoleonic France established a sizable quasi-unitary state in Europe for the first time without the blessings of any Catholic religious authority. It occupied Rome and subjected the Pope to the emperor’s service, a situation seen only with Constantine 15 centuries earlier or Charlemagne a thousand years earlier in the 14th century during the Avignon period when the king of France held the Pope.

England combated this project using its colonies, trade, and superior public finance system. Private entrepreneurs took part in political decisions and taxed themselves to support the crown’s military and political pursuits, as opposed to a system where Paris imposed its will on citizens and territories. The British-led victory over Napoleonic France in 1815 marked another retreat of the Papacy from geopolitics. Napoleon’s defeat hastened the Church’s political decline. In Latin America, Masonic, anti-Papist, anti-Spanish, and anti-Portuguese revolutions dismantled the Catholic Iberian empires. In Europe, new nation-states emerged, weakening the Austrian Empire. It marked the end of the Austrian and Iberian dynasties that failed to prevail in 1648.

The gradual rise of the Italian state in the 19th century at Austria’s expense paralleled the birth of independent Latin American states from Spanish and Portuguese control, the US Monroe Doctrine, and the acquisition of the last Spanish colonies in Asia, such as the Philippines. These events aligned with the global spread of Westphalia’s victorious nations.

This transformation culminated between 1870, with the fall of the Papal States, and 1918, with the Holy Roman Empire’s demise – the end of Westphalian peace’s last vestiges.

Bilateral Diplomacy is Not Enough

In 1870, after defeating the French Empire, Bismarck extended Prussian influence over previously Austrian-influenced Southern Germany, supported the Italian conquest of the Papal States, and constructed a complex network of alliances aimed at maintaining European peace. This structure unraveled when Germany, the primary beneficiary, felt it was constrained rather than secured by the established order. The League of Nations was established after World War I, followed by the United Nations after World War II, based on the belief that mere bilateral diplomacy was insufficient for maintaining a power balance. However, papal mediation was not trusted; an independent organization was required.

Both organizations failed to some extent. The UN’s challenges began in the post-Cold War era when it failed to adapt to a new global reality, leading to its marginalization. Reforming the UN is challenging.

In the meantime, the Papacy’s role is expanding. The Pope re-entered the political arena in the 1940s, aiding the reconstruction of a new Europe alongside Catholic parties in Germany, France, and Italy. Pope John Paul II contributed to the peaceful collapse of the Soviet Empire since the late 1970s.

Today, Pope Francis projects the Church into Asia, adopting a mission analogous to Rome’s role in 5th-century Europe after the Western Empire’s collapse and the Eastern Empire’s transformation. Just as the Church then engaged with the Germanic, Slavic, and Turkic peoples, today, it communicates with the Islamic, Hindu, and Sinic worlds, each with varying degrees of assimilation to Western norms.

The UN’s waning influence underscores the end of the Westphalian balance of powers. We must return to significant historical politics to fully grasp the political stakes necessary for the modern liberal society that has led to extraordinary growth in history. Over the past 150 years, the global population has multiplied tenfold, the average human lifespan has tripled, and the quality of life has improved remarkably.

Frederick Feldkamp noticed that at the center of this change is the United States, now 26% of the global GDP and over 60% of the global listed markets. Most of the money for old and new enterprises goes to America, believing it is and will be the cradle of future growth. Trump’s announced rejection of extreme woke ideology, his call for liberal values and deregulation, balanced trade, fiscal responsibility, and awareness of historical shifts reflect this. America is changing, and so is the world.

Trump envisions a recalibration of power akin to the Roman Empire, with America as the center and other countries in a differing order. A key element here is diplomacy. Unlike the Chinese Empire, which was ruled by clear and direct administrative and power structures, the Roman and Holy Roman Empires were managed through a complex cobweb of commands, alliances, finance, and cultural influence. The US empire is similar. Of course, we shall see if Trump will deliver on his many promises, but so far, the markets, a potent indicator, trust him.

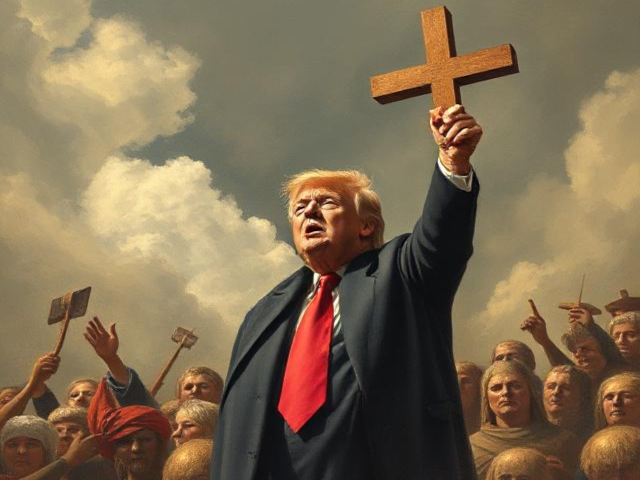

The America that elected Trump is no longer “anti-Papist” as it once was. Collaboration against communism has strengthened ties with the Church. Notably, before the vote, Trump attended Cardinal Dolan’s conference in New York, while democrat candidate Kamala Harris did not. A new relationship between the Pope and the ruling empire is perhaps being forged. In this context, the Papacy is no longer that of the 5th century.

The multiracial Germanic Empire that arose subsequently effectively combined new political vitality with ancient traditions. America now appears poised to do the same.

But now, the presence of many ambitious nations does not guarantee that America will dominate the world for the next century. The nation that best manages the successful liberal model propelling modernity has the best chance, which is currently the United States. To outcompete the US, the EU, China, India, or Russia should establish a superior liberal system, which is currently not the case. Each should consider the Holy See’s unique global influence.

Simultaneously, the US must continue creating opportunities for all. With the advantage of attracting global talent, it must also address its population’s health and educational deficiencies. Basic literacy, numeracy, and historical and geographical knowledge are essential for students after primary school.

Investing in better basic healthcare and education constitutes the best infrastructure for the nation. While deregulation fosters business startups, it also needs fundamental healthcare and education. Implementing antitrust laws is necessary to ensure free competition.

Nothing is set in stone; quite the opposite. Many things can change. For now, despite its many shortcomings and problems, the US appears in a good position. Other places have different advantages, enormous stamina and determination. It’d be naïve to believe the United States will necessarily emerge victors in the present geopolitical game. It needs a comprehensive political plan for the future, which it apparently doesn’t have while others do. The clarity of an endgame is always an advantage in politics.

Thanks to Marcello Neri for his advice and patience

Grazie per i Tuoi articoli e la Tua visione che ritengo moto appropriata. Continuerò a leggerti con piacere.