The US may have better political conditions for a battle against Beijing than 25 years ago. They may be more important than the Chinese military progress. But it’s very subtle.

President Donald Trump engaged in a battle with Congress, which led to the risk of a government shutdown in the United States. As we write, the shutdown has been averted, but the message remains. It may also say to foreign governments: “I’m not afraid of a bitter fight with my people; I’m even more ready for a war with you.”

While there’s the possibility that Trump might relent, so far, it seems unlikely. In the same hours, he pledged to continue to support Ukraine in its war against Russia, but it demanded that European countries perk up their military expenditures to 5% of GDP. It could change the EU welfare state and its economic structure, but it could also regear the old continent to new defense needs beyond Russia or the Middle East.

The message is aimed at Iran and Russia, with which the US indirectly engages in conflict, and signals China.

How will they interpret the message? Will they show flexibility or be more confrontational? During his campaign, Trump promised high tariffs on Chinese exports, but some believe Washington might back down because it would be too costly for America.

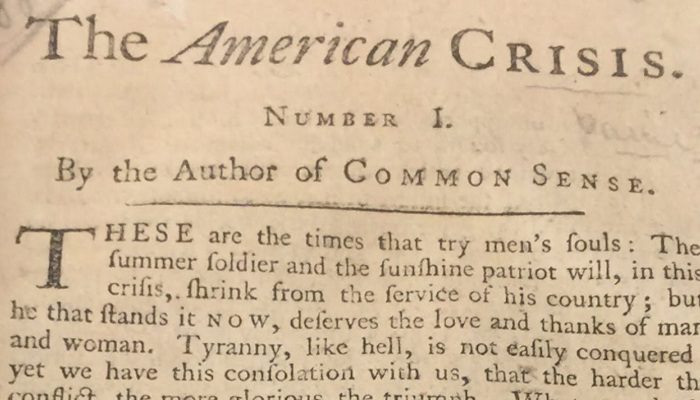

It’s a vast quandary that may reinforce the argument that America has wasted 20 years by not tackling China sooner. Some believe the US should have concentrated on China in 2001 after the 9/11instead of pursuing Muslim extremists, who are considered less of an existential threat.

Thomas Friedman[i] reports on China’s significant advancements in manufacturing and technology in recent years. Beijing is preparing for American tariffs by improving its production quality and planning to use other countries as a base to re-export to the US or the EU. It can be seen as a strategic buildup in preparation for a potential trade/cold war.

Over two decades after 2001, China is wealthier, stronger, and more technologically advanced, making it harder to cope.

Different Angles

However, this perspective might not fully capture the situation. Perhaps, from a different angle, the United States also gained precious time.

In 1989, during the Tiananmen demonstrations, millions of Chinese showed they felt they had little to lose. Ten years later, many Chinese protested against Americans following the bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, despite government bans. At that time, most Chinese had little to lose, so revolution or war seemed like an opportunity for social advancement. Protesters in 1989 and 1999 typically had siblings but no home, car, or bank account. A revolution or war offered a chance to change their fate. Large families can afford the loss of one son in the war, but families with single children can’t.

A tough row with the US then could have easily slipped into a war that could have led to a bloodbath. While America might have won it, the political consequences could have been contentious. A massive loss of Chinese lives could have deeply affected American and global conscience and image. Furthermore, after losing so many people, China could have repealed its one-child policy (which started in 1980 to stem explosive and expensive demographic growth), allowing the population to recover with a newfound animosity towards the US and the West.

Today, the situation is different. The Chinese have experienced 45 years of the one-child policy, and those under 50 have no siblings but feel well off with assets like homes, cars, and bank accounts. For them, war or revolution no longer represents a chance to improve their lives but a risk of losing everything they have.

Moreover, the US has shown the Chinese over 50 years of patience and generosity that it does not mean harm. During this time, China has flourished like never before, and many don’t fully believe that the US is against them. Thus, now, a Chinese defeat in a short clash could trigger Beijing’s political upheaval.

Additionally, the broad context has evolved. In the late 1990s, after the 1997 financial crisis, many Asian countries supported China, but now, due to Chinese policies, many have aligned with the US. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has brought Europeans closer to the US, and conflicts with Muslim extremists have paved the way for the Abraham Accords, which are reshaping geopolitics in the Middle East.

Militarily, China is more challenging for the US, but politically, it makes more sense now.

Not a straight line

There are also lost occasions for China. If China had reformed its finances over the past 20 years, made the RMB fully convertible, initiated political reforms, allowed some elections in Hong Kong, and strengthened ties with Asian countries, as it seemed possible in 2002-2003, the world might have evolved into a G2 (US-China) dynamic.

It might be a genuine lost chance for China because, as we can see, it could be a better time for the US to face a war with China than in 2001.

Beijing likely knows this and is preparing. It has ended its one-child policy for its declining demographics and martial preparations. The end of the one-child policy could lead, in a few decades, to larger families willing to send children to war. Anti-American propaganda is cultivating social opposition to the United States, and economic contraction is creating social classes more inclined to view war as an opportunity for advancement.

This program presents the US with a short-term opportunity for a minor, yet politically impactful, conflict with Beijing.

However, ongoing hostilities in Ukraine and the Middle East distract the US, making it difficult, but not impossible, to face China alongside Russia and Iran. These feuds may help China buy time, but they are risky. When they end, China could find itself more isolated. They are draining Chinese resources and embitter ties with Europeans and other US allies. Plus, they are a deterrent against Beijing, showing US determination.

However, propaganda can play a critical role, as anti-Israeli rallies become banners against Western “colonialism.” Plus, discontent over the Ukrainian war, global weariness with the G7, the small club of the ultra-rich, the rapid expansion of BRICS, and discussions, although symbolic, about an alternative to the US dollar are elements that Russia or China do use to demonstrate that the US is under pressure and weakened.

Chinese officials may not perceive themselves as losing ground; they see divisions within the US and between members of the Western alliance and boast about the advances made against US dominance.

For the US and its allies, tackling all these challenges simultaneously suggests that the issue isn’t only China but shaping a new world order, a concept still uncertain beyond “China’s handling.”

The uncertainties are leverage China can use in seeking an agreement with the US, albeit elusive. Chinese leaders fear an imbalanced agreement could undermine their authority so that they may remain firm. Trust issues make any agreement’s formulation uncertain.

Absent a sudden conflict, a standoff could last years or even decades. China and the US are seemingly preparing for either scenario.

[i] https://www.nytimes.com/2024/12/17/opinion/us-china-musk-swift-tariffs-manufacturing.html?smid=nytcore-ios-share&referringSource=articleShare