There’s nothing particularly new about a gathering of Christian ministers praying around U.S. President Donald Trump to bless him before the flashlights. Pastor Paula White-Cain was appointed to head the White House Faith Office. It happened, and it is happening again—for once, in a very imaginative and surprising start to the presidency, the scene wasn’t particularly inventive.

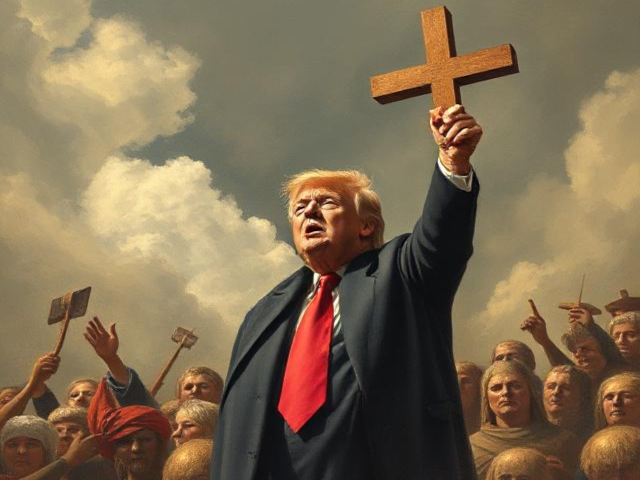

There is only one deviation from the script of the first term eight years ago. His second term appears to have a more messianic interpretation. But it isn’t just his own: without the two attacks on his life during the electoral campaign, Trump could not have been seen by some as an American Messiah sent by God to inaugurate a new era of American greatness. In any case, messianism too isn’t new in the conscience of the American nation.

Whether Trump really believes in his messianic vocation or whether it is simply a tool of his rhetoric doesn’t change the issue much. Yet, as Catholics, if it were the former, the critical judgment of American religiosity should become a little more attentive about Trump’s supporters, and it lends credence to his detractors.

Discerning

Churches and every single Christian have the power to discern Trump’s policies in the light of the Gospel: recognizing or not recognizing their actual adherence to the values carried forward by Christian traditions. The United States’ political history is also made up of the oversights and omissions of this power of discernment given to Christian citizens by their faith.

Today, as in the past, the outcome of such discernment will weigh on the responsibility of each believer. Bearing in mind that, based on one’s faith and moral principles, one can neither reject Trump and the policies of his administration in their entirety nor support them totally without reservation. What religious discernment can and must do is to decide whether and how to support Trump’s policies. Above all, it’s crucial to argue why one should support them even when it means going against the choices of other believers on the grounds of the same faith (and vice versa).

One can be totally for or totally against Trump only if one avoids this conflict of conscience that Christian faith is called upon to face. Or one can be totally pro or contra for entirely worldly interests—possibly disguised by an aura of Christian religiosity. But when one does this, one gives to the Caesars of this world the honor that belongs only to God—on this matter, the Gospel is clear.

Pope Francis on the US

An example of discernment and responsibility without falling into supine subservience or stubborn opposition is Pope Francis’ letter to the American Catholic bishops—letting them know of his support for the criticism they have voiced against Trump’s plans for the mass deportation of undocumented immigrants.

«The rightly formed conscience cannot fail to make a critical judgment and express its disagreement with any measure that tacitly or explicitly identifies the illegal status of some migrants with criminality. At the same time, one must recognize the right of a nation to defend itself and keep communities safe from those who have committed violent or serious crimes while in the country or prior to arrival. (…) An authentic rule of law is verified precisely in the dignified treatment that all people deserve, especially the poorest and most marginalized. (…) This does not impede the development of a policy that regulates orderly and legal immigration. However, this development cannot come about through the privilege of some and the sacrifice of others. What is built on the basis of force, and not on the truth about the equal dignity of every human being, begins badly and will end badly» (Pope Francis).

By supporting the American bishops in this way, Pope Francis argues within the developing framework of the constitutional and legal tradition of the United States. He enters the folds of the founding soul of the nation, even if and when they disagree with the pope on political issues.

State of Exception

The alternative to Pope Francis’ position on immigration in the U.S. is the tacit application of a «state of exception» becoming the habitual form of the American president’s executive powers. Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben worked on the «state of exception,» and in this case, it could be understood as the executive power in its maximal extent. A partial use of the «state of exception» has been applied many times before Trump—by both Democrat and Republican presidents.

The actual implementation of the «state of exception» by Trump’s administration, and not just its rhetorical use in presidential speeches, should be carefully monitored in their civic duties by citizens, Congress, and the Supreme Court. They should pay particular attention to both its extent and its actual use. Once the genie of the «state of exception» has come out of the lamp of democracy, there is no way to put it back in.

In American democracy, the «state of exception» is always constitutionally latent. It means it is always possible to use it to its maximal extent as a legitimate way of exercising the president’s executive power granted by the Constitution. One does not have to suspend the law to declare the «state of exception» in the United States.

A Religious matrix

Both in Agamben’s philosophical approach and in the constitutional history of the United States, such a «state of exception» has an undoubtedly religious matrix. It is on this matrix that theologies should invest their critical judgment as well as their sound insight, without getting lost in diatribes that, presently, may be secondary.

However, it seems that theologians are being seduced by the siren song that is trying to conceal what is theologically really at stake now: whether there is a third option between the wearing out of a democratic era and the future of a new democracy. Surprisingly, today both possibilities have a strong messianic feature.

There are some good theologians who are ready to challenge in a duel the so-called «prosperity theology.» By doing so, they are leaving unattended the field where the world order is being played out—and with it, the destiny of peoples and countries.

Those who need a prosperity Gospel to religiously justify their wealth and well-being by giving up most of humanity as irrelevant to the Christian faith show a deep problem of conscience. It shows how much their wealth and well-being are a huge problem for their own conscience.

Furthermore, a theology exalting the destiny of a tiny minority might be a good placebo for their troubled nights, but it doesn’t work to conquer a world ruled by poverty, not wealth, and bending it to God’s reason.

When, according to the prosperity Gospel, most people are poor, thus not blessed by God, then the “prosperity God” will never become their God.

The «prosperity theology» is the private business of a very few, however influential and strategic they may be. Of course, they could buy the world (and perhaps also the people), but Faust’s tale should be a warning to them. Political hegemony, as defined by Gramsci and as the history of the Church and many religions prove, is not a matter of money but of ideas and ideals, which then can move money. It’s not the other way around. The theological prosperity project could become a despotic ruling of the few over the many, but it will never be culturally hegemonic.

The common good

At this moment, theology’s concerns should therefore be different. They should be about the common good and the «constitutional state» that old Europe was able to forge between the first and second post-war periods in the 20th century.

From a continental legal point of view, the United States is not a «constitutional state»; instead, it is a democratic experiment in its own right—but whose destiny has global repercussions. Europe does not have to be estranged from the U.S., nor mimic its way of being or its politics; but Europe must learn to understand and constructively deal with American exceptionalism—also about the «state of exception» in American style.

Then, two American issues seem to be decisive for our time: the presidential exercise of executive power to the fullest extent granted by the U.S. Constitution; and the use of political institutions to “privatize” the government of the nation. Both issues are not only calling theology to enter the scene of public discourse but also have a theological frame within American political history—which cannot help but be, even today, a religious and Christian history.

ends