Different cultures see and represent reality differently. The West was keen on strict realism: reproduction of the naked anatomy of a body and of realistic visual perspective.

China was more interested in representing the emptiness and symbolism of the mind. Different forms of representation entail different approaches to dealing with reality.

Cultures of strategies, and dealing with war

Anatomy and perspective led to confidence in the ability of men to control, reproduce and perfect their own personal reality, which once free would fall in place in natural order, as with market forces.

The shadow of emptiness required just the opposite. It demonstrated that reality was out of human control and that some external force—the power of the painter or that of a forceful state—had to set boundaries to make it possible to live in it.

Perhaps, strategies are similarly derived from a way of looking at reality. Strategies are possibly not determined by preexisting natural laws that can lead somebody to victory but are grounded on reality’s cultural, geographic perception. They start from the cultural perception of one’s position and then develop from there.

For example, the concept of Thucydides’ trap, now highly fashionable to use when thinking of the confrontation between the US and China, is grounded in the cultural perception of Athens vis-à-vis Sparta in the Greek peninsula. It has the background thinking of a balance of power that can be tipped one way or another.

Conversely, China’s perception of strategy is based on a different premise. The premise is that of a Chinese unity that can be acquired, gained. Once this unity is attained, all other challenges can be managed and overcome. The Chinese perception is born out of the experience of two millennia, founded on the idea that, overall, the Chinese empire was more prominent, with a larger population and greater wealth than all of its neighboring countries put together. Therefore no one country could endanger, the center, China, if the center held its order firmly.

The same is not valid in the West, where neighboring countries didn’t challenge a unitary solid empire. The Roman Empire itself had extended borders that were extremely fragile and, except the one adjoining the Sahara Desert, no natural defense.

The Roman Empire held back for centuries the threat of the Persian Empire, knowing full well that this hazard had to be contained but could not be eliminated because it would stretch the empire over new borders, putting it into direct contact with another perilous realm based in the Indian peninsula. The experience of Alexander the Great who was de facto defeated by its own never-ending successes in an even greater, never-ending world, loomed large in the Roman mind. At Alexander’s death, his vast empire simply shattered into a dozen larger or smaller kingdoms. The world was too large to conquer and hold it whole.

This mental realization led to the policy of Roman and Byzantine containment and balance with the Persian Empire. It became the compass of the strategy on the Eastern Roman border.

The containment of the Germanic tribes from the north was also of paramount importance. They could not be conquered and vanquished because new tribes were coming from Eastern Europe anyway. They had to be checked, somehow tamed and managed, but there was no possibility of having a very stable peace because they could imperil at any time a highly vulnerable and weak northeastern border.

The centrality of the empire was a sea, the Mediterranean. It was linked to a system of sea transportation that included the Red Sea and the Black Sea, which were dominated by Romans at a certain point, and also extended to the Caspian Sea over the Caucasus.

Then it was not a defined space; its borders, the limes, described the land around this space, but it was held together by a highly efficient system of transportation and roads that still hold together the standard for transportation nowadays. The standard train gauge has been de facto fixed by the space occupied on a road by a car driven by two horses side by side.

The Roman Empire, in other words, although it was an empire, had to manage the borders, and any given challenge could threaten the unity of the kingdom: the Persians or the new Barbarians coming from the edges, be they the Germans, the Slavs, the Huns, or the Arabs.

In this way, the idea of balance of power was also inherited by the Roman Empire, and the imperial system in the West has a premise unstated of complete reason.

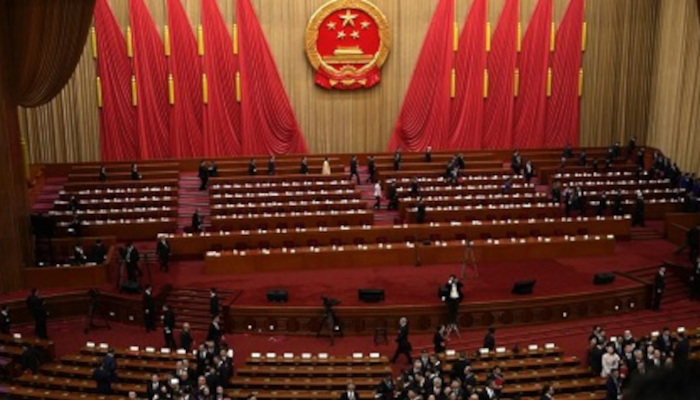

China’s fissures

The underlying Chinese assumption was somehow different. The steppes were too vast and too sparsely populated to gain full control of them and of their population. These were to be held in check by a system of tributes in which, in theory, these tribes recognized the suzerainty of the son of heaven by offering gifts and gained back more than they gave.

Actually, the emperor paid off the border thugs with some kind of protection money and held them back with the threat of ruinous retaliation. The empire said actually, take this money and be happy or we shall attack you. In reality the empire knew that the “protection money” was cheaper than mounting a full-scale attack.

Then China had not a mental block, but a very physical block. It was surrounded by borders that were all similar to the Sahara Desert for Rome. The borders had to be managed but rarely constituted existential threat. Or they were existential only if the imperial unity was in jeopardy to start with. Then the unstated assumption for China was conversely holding the center, keeping the country together; if that was achieved, nothing else could be challenged.

The reality of Chinese geography has changed presently. As China gained complete control of Tibet and ended the independent existence of the territory as a buffer state/zone between the Chinese and the Indian empires, and with the encroachment of the West after the conquest of the American continent by the Spanish and the English, Beijing’s land perception and defense demands changed completely.

Now China is part of a larger world where it is just a tiny minority compared to the rest. It is about 20% of the population, and 15% of the global GDP. Furthermore, it is also a minority in its neighboring areas. All the next-door countries put together—India, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam, Japan, Indonesia—are larger economically and as a population than China.

This creates a different reality for China, while the cultural perception in China remains the same. China still believes that if it manages to control its neighborhood, home to 60% of the global population and 70% of global economic growth, it will eventually dominate the world.

China, consciously or unconsciously, doesn’t see its grand strategy as one of keeping a balance of power, managing the rising or waning powers at its rims. It sees it as one of gaining a significant foothold in a substantial part of the world, and from there repeating and extending its 2,000-year model of ruling. That is, putting the Chinese empire at the center, and keeping more or less at bay the rest of the world, which will not be a challenge if the center holds strong.

This theory is critical in understanding what China is doing and what it is doing wrong for its own good. To achieve this dominating power, China should have done two simple things: win over the two more considerable economic and demographic forces at the borders (Japan and India), and prepare for some kind of political reform that would have made the Chinese political system more palatable to its neighbors and the rest of the world, which is used to a more liberal structure of rule.

That is, China should have tried to expand its political footprint peacefully, and it should have tried to assuage global political fears about the harshness of its political system. It didn’t do either for whatever reason that we shall ignore now.

China, on the contrary, managed to antagonize both India and Japan and didn’t make its political system more palatable; it made it more indigestible. Its economic system didn’t become more integrated into the world, which could have turned it into the hub of economic and global trade. It made itself more closed. It did that by constantly refusing to have the RMB fully convertible or thoroughly reforming its financial system. In this situation, China defeated itself and made its strategic victory eventually more difficult.

Still things are far from decided in the present predicament.

China in imperial times was held together by a system of roads and canals that made internal communication easy and convenient. The Chinese strategy of the new Silk Road was basically to extend its traditional road system to the Eurasian landmass and reach out to Europe as Europe had reached out to China before the discovery of America.

With the outline of the Silk Road, China de facto marginalized, or at least attempted to, the American continent and tried to regain the centrality of Asia, Eurasia, and therefore of Beijing. The system and the strategy are failing because it ignored the central part of the continent, the Indian subcontinent, and the Japanese technological powerhouse. Therefore, the agreement of Europe and the new approach to the weak Central Asian and Middle Eastern countries could in no way outweigh the opposition of so many mighty countries.

But the idea of One Belt, One Road took in a European concept of power that China may have entertained in the early 15th century but abandoned soon after: that of becoming a maritime power. China realized that in the present world, it needed a sea outreach to counter the current American ocean presence and thus it had to follow in the steps of the European powers such as Spain, Portugal, the Dutch, the English, the French, and the Americans.

The attempts to gain maritime footholds were based mainly on surrounding India. Sri Lanka was lured, and Pakistan was also brought in. Both were promised port facilities for Chinese naval ambitions, and so was Myanmar. In this way, India was surrounded on all fronts; in the north, there was China itself; in the west, there was Pakistan; in the east, Myanmar; and in the south, Sri Lanka.

Roman roads for America

Therefore, India could be subjugated and forced to give in. If India were to surrender, China would gain political-military clout in Asia and from there everything would be downhill.

However, a strategy like the famous game of Go must be followed by looking at the bigger picture. In this case, while China was trying to surround and besiege India, India moved out of its predicament by striving to develop ties with other countries and then encircle China itself.

India contacted Japan, Vietnam, Australia, and the United States to present its situation as proof of Chinese global ambitions and global threat. Therefore, it contributed to the push against China.

In this game of reciprocal siege, there are many elements to consider carefully. The game is not over; India is not a strongly unitary country. It is ridden by factional infighting, differences of castes, religions, and ethnicities. There is an active guerrilla movement and riots kill people by the dozen every other week. It confronts many dangers and challenges in pursuing confrontational politics with China and an alliance with these countries. Moreover, premier Modi’s attempt to mold a new unitary Hindu identity may worsen underlying clashes.

Still, as China had tried to learn from America to build up a maritime power, America is presently thinking of taking a page from China’s Silk Road strategy to build an infrastructure network to bolster its global political footprint.

President Joe Biden named it B3W, Build Back Better World. As the Roman Empire managed its sea control also thanks to a network of roads, America is considering the possibility of sponsoring a network of railroads throughout the world, avoiding China and its allies.

The global oceans are apparently for America what the great Mediterranean was for Rome. This would extend its financial and cultural soft power worldwide, bringing new sources of development and growth. Furthermore, America may support this newly established anti-Chinese alliance and transportation network with its technology, arguably still the most advanced.

Here there is a difference with China. As China tried to extend its maritime power while there was an existing active maritime power and therefore contrast directly with it, America’s new railway network would just fill a void. China’s ideas of a new Silk Road barely took off, and presently there is no alternative to an American-sponsored global network of railway systems.

This concept, however, could help deeply alter the American way of thinking about its strategy. The United States may start gradually thinking of strategy no longer as part of a design of balance of power to be managed through a system of contacts, networking, and friendship.

America could de facto start thinking of controlling its power base at home, the American continent, and from there mark its political footprint on an American “Tianxia” (All Under Heaven). That is, America would be the central state, the “Zhongguo,” and the rest of the world, its periphery.

America would be better off than China in doing this because it is an incumbent power. It has a more palatable political system and a multiethnic social system to absorb people and ideas from different ethnicities. Therefore, it could marginalize and eventually end the historical strategy of China.

There are different perceptions here at work and different strategies stemming from these different perceptions, and America has objectively many difficulties as China. It is difficult to think about being a central power and the rest of the world as All Under Heaven, and it’s challenging to balance it with the traditional Western theory of balance of power.

Here we may find another twist. Chinese and Western strategists are fond of studying Sunzi as a paramount military theoretician. However, Chinese traditional strategy is possibly better represented in Mozi, who was the first to introduce technical operational methods for warcraft; defense preparations against sallies, inundation, tunneling, or attack with ladders; and organization for commands signaling.

Mozi put that together with a comprehensive system of statecraft to effectively withstand enemy attack and the first comprehensive study of logic and physics in ancient China. Mozi’s contributions are often neglected in China but seeped through the pores, and its tradition has possibly provided a logical well to think of a statecraft system to oppose an attack.

China may want to think about what could be learned from Mozi today.