The Rejecting, the Skeptical, and the Accepting: From Matteo Ricci’s World Map to the Influence of Missionaries on Late Ming Chinese Scholars

1. Matteo Ricci’s World Map: Its Significance from an Intellectual History Perspective

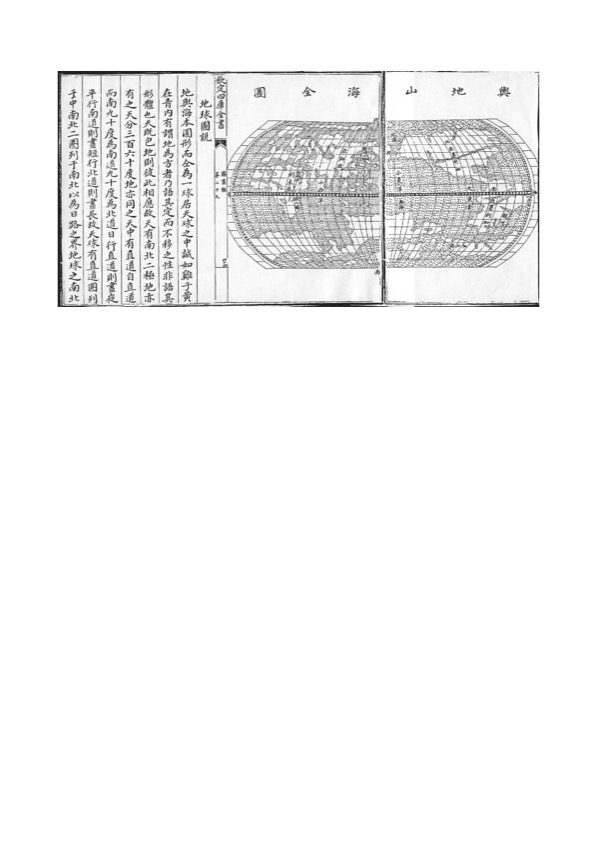

In 1584, shortly after arriving in Zhaoqing, Guangdong, the Italian missionary Matteo Ricci (1552–1610), with the support of the local prefect Wang Pan, printed the Complete Map of the Mountains and Seas (Shanhai Yudi Quantu). This was the first European-style world map printed in China, presenting the most up-to-date geographical knowledge of the time. The map included not only Europe, Africa, and Asia but also the Americas, discovered the previous century, as well as China, Korea, and Japan. Although it placed China at the center, unlike traditional Chinese maps that depicted China as an infinitely vast land, it accurately represented China’s proportional size and position in the world.

As I discussed in Intellectual History of China, from the perspective of intellectual history, the significance of this map lies in its introduction of a new worldview that shattered traditional Chinese notions of tianxia (All-under-Heaven). It emphasized that the world consisted of many nations, that China was not at its center, and that it was certainly not the only boundless empire. At the time, many conservative officials vehemently criticized the map, accusing it of exaggerating foreign lands while belittling China, dismissing it as absurd fabrication. Yet, many intellectuals, such as Xu Guangqi and Li Zhizao, embraced this new worldview. Interestingly, the Wanli Emperor also took a keen interest in it. Without delving deeply into the profound implications of this altered tianxia image, he happily commissioned a large-screen version of the Kunyu Wanguo Quantu (Complete Geographical Map of the Myriad Countries of the World) for the imperial court. This effectively granted the map official endorsement. Consequently, from the late 16th to the 17th century, various world maps based on Ricci’s work proliferated—at least twelve versions survive today.

Ricci himself admitted that his map had an agenda: to dismantle China’s sense of superiority and encourage acceptance of Catholic civilization. He wrote, “When they see how small their country is compared to many others, their arrogance may diminish, and they may become more willing to engage with other nations.” Indeed, ancient China’s interactions with foreign states were framed in hierarchical terms—tributes, investitures, audiences, or policies like “pacifying barbarians”—with little notion of equality or pluralism. As early as the 6th century, when envoys from Japan arrived in Sui China, the phrase “the King of the Land of the Rising Sun greets the King of the Land of the Setting Sun” in their diplomatic correspondence displeased the Chinese emperor. Even in the late 18th century, British envoy George Macartney’s audience with the Qianlong Emperor sparked disputes over protocol and rank. Similar debates arose when missionaries arrived, often clashing over diplomatic “etiquette.”

From the perspective of Chinese intellectual history, Ricci’s world map raised profound conceptual questions because it conveyed to the Chinese:

- The world was no longer flat but spherical.

- The world was vast, with China occupying only a tenth of Asia, which itself was just a fifth of the world. China was not an infinitely vast empire but rather a small part of a much larger whole.

- Traditional Chinese notions of tianxia (All-under-Heaven), Zhongguo (Middle Kingdom), and the siyi (Four Barbarians) were untenable. China was not necessarily the world’s center, and the so-called “barbarians” might themselves be civilized nations that viewed China as peripheral.

- It was necessary to acknowledge the equality and commonality of all civilizations and to recognize universal truths transcending nations, borders, and ethnicities.

2. Resources for Changing Tradition: The New Knowledge Brought by Missionaries

From the mid-16th century onward, European missionaries arrived in the East in waves. By then, Europeans had already discovered the Americas, navigated around the Cape of Good Hope to reach India, and sailed through the Strait of Malacca into the waters of the East and South China Seas. Among these Europeans, three groups were most significant: merchants, colonizers, and missionaries. Merchants traded American silver for Southeast Asian spices, Chinese silk, porcelain, and later, tea. Colonizers seized coastal ports and islands as bases for plundering resources, establishing warehouses, and facilitating trade before pushing inland to claim territories as colonies. As for the missionaries? They served God, aiming—in their words—to “civilize” the “uncivilized” East with Christian faith.

From the mid-to-late Ming Dynasty, starting with figures like St. Francis Xavier (1502–1556), Matteo Ricci (1552–1610), Niccolò Longobardo (1559–1654), Diego de Pantoja (1571–1618), Nicolas Trigault (1577–1629), and Giulio Aleni (1582–1649), waves of missionaries came to the East for this religious mission. However, in the process of proselytizing, they inadvertently introduced Western ideas, knowledge, and technology to China, which gradually began to erode the foundations of Eastern civilization.

By “gradually,” I mean this erosion was not sudden but rather a slow process. True transformation in China only came in the mid-19th century, when the shock of European gunboats and the existential crisis they provoked spurred rapid, radical change—shifting China from “change within tradition” to “change beyond tradition.” Only then did foreign ideas, knowledge, and beliefs flood in, forcing traditional China to modernize. But in the late Ming and early Qing, when missionaries first arrived, new ideas, beliefs, and knowledge were initially absorbed as “resources,” reinterpreted through a local lens, and only then integrated as adapted forms of “civilization.”

This was a protracted process. The native tradition—old ideas, beliefs, and knowledge—was imperceptibly reshaped through this intermingling. The resulting cultural tradition was neither entirely new nor entirely old, neither purely foreign nor purely indigenous. To reiterate: foreign civilization entered as a resource, was reinterpreted, and seeped into tradition, transforming the old into the new. In times of crisis, this process accelerated, shifting from gradual to abrupt. Cultural transmission often follows this pattern.

3. The Rejecting, the Skeptical, and the Accepting: The Different Fates of Three Types of New Knowledge

The new knowledge brought by Western missionaries at the time can be roughly divided into three categories.

First were practical knowledge and technologies, such as European hydraulics, firearms, medicine, geometry, and even calendar systems. Because they “furthered practical learning and benefited the world” (in Li Zhizao’s words), these were the most readily accepted. Li Zhizao, in a memorial to the court, proposed translating works on hydraulics, mathematics, astronomy, sundials, medicine, musical instruments, natural philosophy (gewu qiongli), and Euclid’s Elements. Why? Because “these diverse techniques, though varied, all accord with Heaven.” Aside from some “frivolous novelties” (qiji yinqiao—useless luxuries), there was little resistance to adopting them. Historically, China had absorbed foreign goods and technologies (like sugar refining or horse breeding) from Persia and the Islamic world without political or cultural barriers.

Second were new ways of understanding and interpreting the world, particularly concerning “Heaven” and “Earth.” These were especially problematic yet crucial. While they appeared as knowledge, they carried underlying—and profoundly significant—worldviews. Conversely, while they were conceptual, they relied on empirical support; without alignment with experience and perception, these ideas would collapse. Two key aspects stood out:

- Theories about “Heaven”: Was the sky round and the earth flat, or was the earth spherical? This was not just an astronomical issue but also touched on the foundations of ancient Chinese political culture and the sanctity of imperial authority. Traditional cosmology held that the sky was like a canopy, the earth like a chessboard, with the North Star eternally fixed and the imperial throne at the center—mirroring the state’s ruler, surrounded by stars like subjects. This natural order reinforced political order. But missionary teachings about a spherical earth and heliocentrism upended this cosmology, destabilizing the sacred, fixed hierarchy. As French scholar Jacques Gernet (China and Christianity) and Japanese scholar Yabuuchi Kiyoshi (Chinese Astronomy and Calendrics) noted, China’s shift from geocentrism to heliocentrism was revolutionary, affecting not just astronomy but also spiritual paradigms.

- The nature of “Earth” (the world): Was China the vast center of the world, or were there five continents with countless nations, some equally civilized? This challenged China’s self-perception and its view of outsiders (hua-yi distinctions). Missionary knowledge introduced the idea of five continents, numerous nations, and even antipodal peoples, undermining the myth of China’s incomparable grandeur. Xu Guangqi not only endorsed world maps but also proposed crafting a wooden globe, which would subvert traditional cosmology. How, then, could China sustain its celestial empire (tianchao) and tianxia worldview? Historically, China had relied on these concepts, along with tributary or investiture systems, to maintain its confidence, dignity, and international order. But now, what was China to do?

Third were new religious, political, and social ideas, chief among them Catholic doctrine. Concepts like the supremacy of God, unconditional worship, and the separation of secular and sacred authority (“the ruler governs, the Pope teaches”) were hard for China to accept. Although some, like Xu Guangqi, Li Zhizao, and Yang Tingyun, embraced Catholicism, most elites and commoners resisted. Why? Traditional China upheld the absolute authority of the emperor, with political power supreme and intolerant of rival religious authority. Medieval debates over whether Buddhist monks should bow to the emperor (shamen bu jing wangzhe) showed China’s unwillingness to accept a religion sharing power with the throne. Catholic notions of God, the Church, and papal authority were unimaginable in China. Moreover, Confucian-Legalist traditions reinforced imperial hierarchy through ethics and law, leaving no room for a religion claiming moral and social authority. Anti-Catholic texts like Poxie Ji (Collected Exposés of Heterodoxy), compiled by Xu Changzhi, illustrate how difficult it was for such ideas to take root.

4. Conclusion: How Was Traditional China’s Intellectual World Transformed as a Whole?

In short, when traditional China encountered Western knowledge brought by missionaries, these three categories met different fates.

- Practical knowledge and technology were easily accepted due to their utility, facing little nationalist or imperialist resistance.

- Conceptual knowledge faced more hurdles, as its deeper implications threatened to alter values and worldviews. Yet, because its influence was indirect, opposition was less fierce.

- Religious and political ideas clashed directly with Chinese tradition, challenging or endangering its foundations, and thus met fierce resistance from the outset.

Looking back at modern Chinese history, we see this pattern repeat in the late Qing: first, adopting Western technology (“learning barbarian techniques to counter barbarians”) for practical use, which alone could not withstand Western impact; next, absorbing new knowledge of astronomy, geography, and history, which destabilized traditional intellectual systems, prompting the zhongti xiyong (“Chinese learning as essence, Western learning for utility”) compromise; then, institutional reforms, shifting from zhongti xiyong to xiti zhongyong (“Western learning as essence, Chinese learning for utility”); finally, a full break with tradition and wholesale Westernization in the early 20th century—a “transformation unseen in two millennia” that the Ming-Qing missionaries could never have imagined.

Lastly, a brief comparison of how China and Japan differently received missionary culture. Japan uses two terms: junyō (受容, acceptance) and hen’yō (変容, adaptation). The former means absorbing foreign culture; the latter means modifying it in the process. Studying Edo-era Japan, one notices key differences from China:

- Decentralized power: Unlike China’s centralized empire, Japan’s shogunate and emperor shared authority, with regional lords (daimyo) and local autonomy creating space for Catholicism to spread.

- Pluralistic traditions: Japan’s mix of Buddhism, Shinto, and folk beliefs lacked the exclusivity of China’s Confucian-Legalist orthodoxy, allowing Catholicism to coexist.

- Pragmatic adoption: Japan, long accustomed to borrowing culture, lacked rigid traditions and embraced Western medicine, anatomy, botany, firearms, and navigation without needing holistic justification (e.g., using katakana for foreign terms).

In contrast, China fixated on astronomy, mathematics, and calendrics, insisting on systemic (ti-yong) integration—why? Why did China demand that new knowledge fit a coherent framework linking politics, economy, culture, and technology?

This logical divergence in how China and Japan engaged with the West warrants deeper reflection.