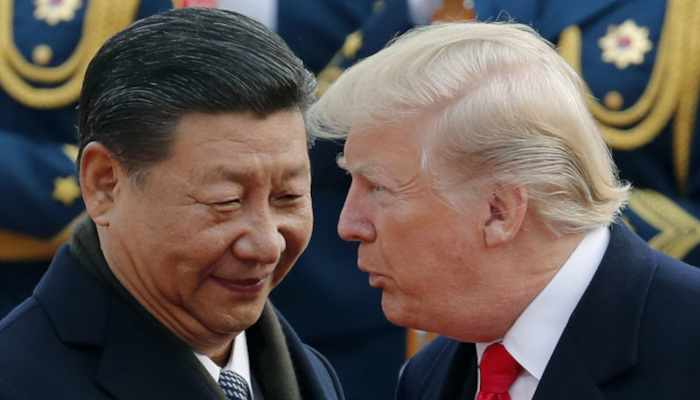

Beijing’s trade and foreign affairs, heavily influenced by tradition, might need a change because of the new Trump policy on the Green Deal

In ancient China, the Ministry of Rituals and Materials (禮品部) functioned as the de facto Foreign Ministry, managing foreign affairs and trade. International relations were strictly regulated, defined by interactions between the imperial court and its vassal states, based on the recognition of China’s central position and suzerainty.

The Ming dynasty’s practice of bestowing gifts exceeding the value of tribute received prompted numerous tributary missions. This created a substantial trade imbalance, leading the Ming court, after 1435, to restrict these missions by discouraging visits and withdrawing logistical support. Delegations were limited to under a dozen people, and the overall frequency of such missions was drastically reduced.[1].

The system was about giving and receiving of gifts. It functioned effectively only while the Chinese court maintained ultimate power. When vassals sensed China’s weakness, they would raid its territory. Also, in times of crisis, much trade ran through different channels out of central government control, like opium during the 1820s and 1830s.

China’s contemporary strategy of using gifts to influence Western business leaders or officials might stem from this historical precedent. The underlying belief is that cultivating relationships through material generosity can secure influence and favor. However, this strategy hinges on a crucial assumption: China’s sustained dominance. A weakening of China’s power, mirroring the historical precedent, could render this approach ineffective.

Gifts, in this context, are not transactional exchanges for goods or services but rather expressions of goodwill, granted or withdrawn at will. They are not immediate payments, but investments intended to yield future benefits. In other words, China had a grip over businessmen as long as the U.S., the global economic gatekeeper and guarantor, allowed China’s grip. With the U.S. curtailing access, China’s overall economic influence waned, consequently impacting its sway over these businesses.

Therefore, major trade and financial disputes between the U.S. and China could significantly undermine this gift-giving strategy, particularly for companies heavily reliant on American goodwill. The U.S. holds the power to pressure both American and international corporations engaging with China, it may essentially force acceptance of Chinese favors without requiring reciprocal benefits. This ability can wield significant influence on broader industrial policy decisions.

The Gift of EV

This strategy has significant real-world consequences. Approximately 20-30 years ago, driven by widespread concerns regarding global warming, the Western world prioritized renewable energy sources like solar, wind, and battery technologies. It had a strategic element: reducing dependence on oil-producing countries. Nations such as Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Kuwait, and Qatar had historically exerted considerable control over the global energy market, influencing prices and policies.

The West’s historical over-reliance on the Gulf states for oil became a major vulnerability following the 1970s OPEC oil embargo. The U.S. mitigated this by importing Russian oil during the Cold War. Renewable energy promised to further diminish this vulnerability.

The recent innovation of fracking technology in the U.S. is changing the game. It has created a surplus in domestic oil and gas production, resulting in a return to oil and gas exports. While fracking is generally more expensive than extraction in Gulf states, a relatively low global supply—exacerbated by factors such as the war in Ukraine—has driven up prices, making American oil production more competitive.

At the same time, renewable energy technologies have not yet fully delivered on their promised potential. Essential breakthroughs in battery technology remain elusive, hindering energy storage capabilities. The limitations in storing and transporting solar energy also pose significant challenges compared to traditional fossil fuels. Furthermore, establishing and maintaining pipeline infrastructure proves more efficient and cost-effective than developing extensive power grids for long-distance electricity transmission.

There is no complete substitute for oil and gas. Batteries have encountered various challenges, and the automotive industry has struggled to catch up. In the Western world, Tesla is practically the only company producing competitive electric cars. The lack of competition makes it difficult for the industry to advance.

The only notable competition comes from China’s BYD, which is politically sensitive. If there were no political sensitivities or contentious issues like Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) theft. If there were an authentic exchange of political goodwill between the U.S. and China, BYD could have emerged as a global competitor to Tesla, potentially revolutionizing the car industry and other sectors.

Substitutes

The decreasing enthusiasm for renewable energy and the accompanying emphasis on its lasting carbon footprints pose a significant threat to China’s renewable energy industry, where it is the current global leader. Maintaining strong and positive relationships with the U.S. would have been crucial for navigating this change.

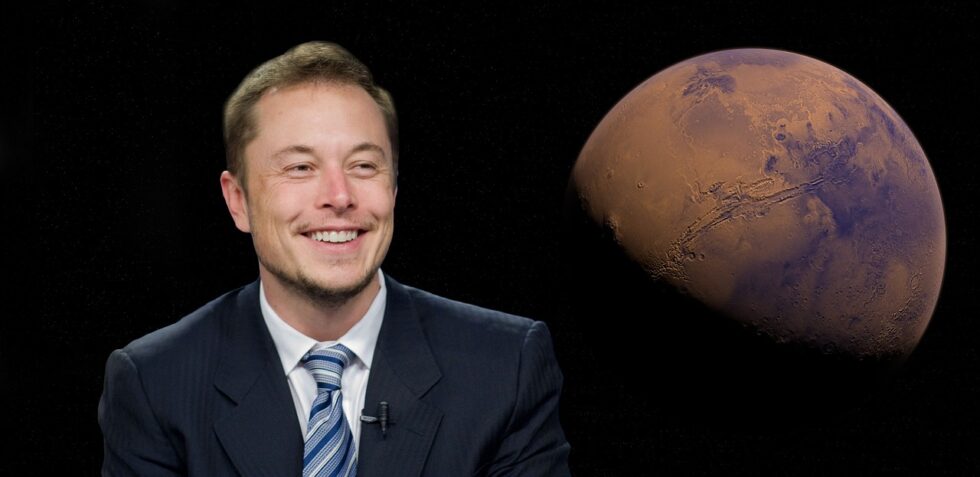

U.S. President Donald Trump, in his inauguration speech, denounced the Green Deal, which underpins all renewable energies and the development of electric vehicles. Tesla is a market leader in this sector, and its chairman, Elon Musk, is possibly Trump’s most important supporter. Tesla generates approximately 40% of its global sales in China, representing a $50 billion business.

However, if the U.S. abandons the Green Deal and pushes for greater use of oil and gas, China’s electric vehicle (EV) technology and solar panel sector may suffer a significant setback.

The global narrative could shift, portraying China as environmentally friendly while labeling America as “coal-black.” This would not reflect well on America’s international image.

Yet, the overall global narrative might shift, arguing that the overall carbon footprint of renewables—without significant technological breakthroughs—could exceed that of oil and gas.

Traditional automakers and those in the oil industry may celebrate this shift, especially in Europe, where EV development lags.

Fracking has significantly altered the energy landscape. While proven global oil reserves (1.6 trillion barrels) would theoretically last approximately 43 years at current consumption rates, untapped oil shale reserves (6.05 trillion barrels) could potentially quadruple the available supply, extending the timeframe to 100-200 years. This extended timeframe provides an opportunity for further technological innovation in alternative energy sources.

Currently, nuclear energy appears as a safer and more efficient solution. Smaller, more secure nuclear power plants could help lower energy consumption, reduce prices, and buy time for renewable technologies to mature. The U.S. maintains a substantial technological lead in both fracking and advanced nuclear power generation.

China’s relationship with Elon Musk might reflect a strategy similar to its approach toward wealthy Hong Kong businessmen in the 1990s. Beijing offered these tycoons substantial economic incentives, consolidating its control over the region. This elevated local Chinese millionaires’ status and influence, surpassing that of their British counterparts following the 1997 handover. Many gained significant monopolies, but this strategy ultimately proved counterproductive. Limited opportunities for young Hongkongers, stagnant salaries, and increased competition from mainlanders fueled significant social and political unrest from 2014 to 2019.

In any case, Hong Kong’s pacification worked because Beijing had ultimate political control. Yet, there were drawbacks because the territory didn’t have a democratic system to help ordinary people vent their frustrations and seek an alternative. Moreover, Hong Kong didn’t fit the dominant and previous cultural-political atmosphere, which fostered a liberal environment conducive to free movements of its market. The overall result was that the Hong Kong Stock exchange, once the third most important of the world, floundered.

This Hong Kong experience offers valuable insight into the potential outcomes of China’s relationship with Musk and the EV market. From Beijing’s point of view, Musk’s position within China (through Tesla), coupled with his relationship to Trump, presents an opportunity for unofficial U.S.-China negotiations. His role could potentially mirror that of the wealthy Hong Kong tycoons before the handover.

However, while China may believe it has a firm grip on him, this may not be the case, as Musk’s investment in the EV future could suffer. This scenario may also apply to all wealthy Americans seeking business in China. They may be granted special access to the potential for Chinese profits in exchange for goodwill in their home country.

Their influence could be diminished if the political landscape in the U.S. or the overall atmosphere shifts. China may need to rethink the instruments and philosophy of foreign affairs and trade at this delicate moment.

Finis

[1] Siu, Yiu (2023), “The Cessation of Zheng He’s Voyages and the Beginning of Private Sailings: Fiscal Competition between Emperors and Bureaucrats”, Journal of Chinese History, 8: 95–114

Musk and China, a Wrong Bet? - SettimanaNews