Italy was neither born one, nor does it have a deep-rooted tradition of political unity. For example, Siena fought Florence for centuries, and within Siena itself, there are still centuries-old rivalries between the districts, the contrade. The nation was forged through the gradual patching and soothing of the rifts created by a political merger, which involved passing through half a dozen wars against both foreigners and Italians themselves.

In 1943, some Italians chose to fight other Italians in loyalty to the Nazis, while soon after, others were willing to side with the Soviets, again against other Italians.

In this fragile terrain, factionalism of language and gestures can create irremediable rifts. It stokes and amplifies contradictions and contrasts, becoming both a symptom and a precursor of authoritarianism. Yet, authoritarianism does not heal a nation; it creates wounds that shed blood everywhere and often ends up destroying those who inflict the injuries.

Moreover, the mere shadow of Italian authoritarianism is chilling. A century ago, Russia first changed regimes and political sides (the Soviets took over), followed by Italy with an opposite but parallel coup (the Fascists came to power). Meanwhile, the desire for dictatorship was growing in Europe, with the Nazi party in Germany warming its engines, poised to obliterate centuries of European history.

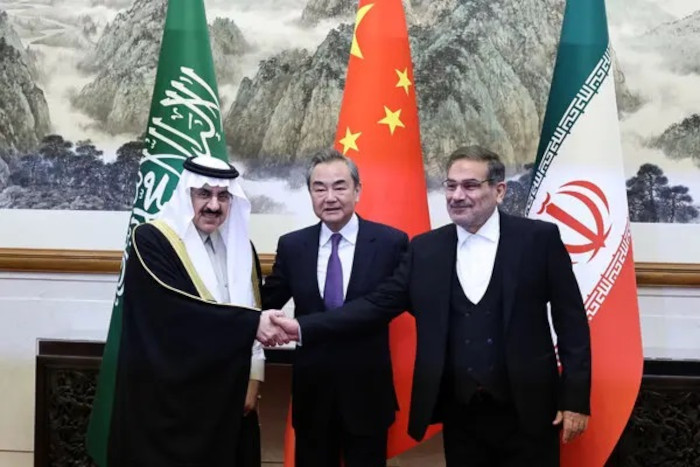

One hundred years later, is the situation very different? In Russia, President Vladimir Putin has gradually steered the country onto a collision course with the West. Like a hundred years ago with the Soviets, Putin’s point of view is diametrically opposed to the Western one; the foreigners made Russian life miserable.

In Italy, a party claiming the legacy of Mussolini has taken power. An authoritarian wind is blowing through half of Europe, and in Germany, the openly pro-Nazi AfD is gaining traction. In Spain, Vox, and in France, RN, appear as the heirs of Franco and Pétain. The reasons for this wave are opposite yet parallel. Then, it was the race to acquire colonial space in Africa; today, it is the defense against migration from those former colonies.

Of course, nothing is entirely the same; the world has changed, and the political dynamics are different. However, there is a deafening echo of the past.

That is why, at least in Italy, it is essential to reflect on the 1950s. In that ruthless period, when Italy was a battlefield of the Cold War, Italian parties remained careful to maintain a sense of nationhood without succumbing to authoritarian temptations. The coalition around the Christian Democrats (DC) did not bow to pressures for an anti-communist coup, nor did the Communists yield to calls for an anti-democratic revolt. Extremist impulses were kept at bay, albeit with difficulty.

Even Silvio Berlusconi and his opponents always sought conciliation, sometimes excessively so, leading to accusations of “consociativismo” (consociation with the opposition).

The M5S’s extreme rhetoric of “vaffa (f***) day” brought a maximalist approach to power: open the can to eat the tuna. Since that time, except for the Mario Draghi interlude, the climate of factionalism in Italy has increased.

Attempting to impose a controversial reform on the premiership in Parliament, especially with a 50% absenteeism rate, by asserting “it’s do or die,” as Premier Giorgia Meloni recently did, is perhaps not the best way to unite an already fractured Italy. Because then it can only go one way: to smash everything. It goes beyond the merits or otherwise of the reform.

Indeed, trying to impose one’s will and ignore opponents’ objections is contrary to seeking mediation and compromise solutions. It resembles Mussolini’s “Better a Lion’s Day.” It looks like a desire for conflict. But in history, those who have sought a lion’s day have often ended up in wars that were ultimately lost.

Personally, I have never been hostile to Meloni; quite the contrary. But in a democracy, the government must conquer, seduce, and convince opponents—there are no enemies except those who want to destroy democracy. Opponents must be approached with respect. Those in government cannot seek confrontation at the risk of destroying everything and themselves.

The lawsuit recently delivered at 4 a.m. to journalist Massimo Giannini is an unnecessary gesture of hostility. It breeds more hostility and increases the system’s entropy, ultimately favoring the opposition and harming the government.

The Italian bishops’ appeals should be a wake-up call. With all due caution and circumspection, the CEI (Italian Conference of Bishops) is increasingly explicit in opposing the reform of differentiated autonomy (granting more power to regions away from central authority), which is only a thinly veiled way of also declaring themselves against the premiership.

In this fragile climate, the government awaits action from the European Union, which, as early as the second half of June, could open infringement proceedings against Italy. The country is in default on its Stability and Growth Pact commitments, and the commission will indicate a three-year return plan that could be very painful. This pain would be salt on the current political and social wounds.

(published in Italian on Formiche.net)

Meloni: un premierato divisivo - SettimanaNews